Completed after 40 years of on-and-off work, Bray’s tribulations were realised in another stunning reproduction, which he loaned to the British Library, and which his estate bequeathed to the institution following his death, where it can be seen today. This time, however, its making wasn’t a matter of years, but decades. Shaken, but not shattered, Bray once again rolled up his sleeves to produce yet another version of his uncle’s swan song. The Great Omar, it seemed, had been born under a bad sign, for, during the London Blitz of World War Two, it was – not unlike the poet’s wine jugs, symbolic of human frailty – dashed to pieces. Using Sangorski’s original drawings, he managed – after a gruelling six years – to replicate the book, which was placed in a bank vault. Sutcliffe’s nephew Stanley Bray was determined to revive not only the memory of the Great Omar, but also the book itself. The story, however, didn’t end with the sinking of the Titanic, or even Sangorski’s strange death by drowning some weeks afterwards. The Titanic was next in line, and the rest needs no explanation.

Unluckily for him – and the world – it couldn’t be taken aboard the ship originally chosen.

Wells, like Sotheran’s before him, intended to have the masterpiece shipped to America. It was returned to England, where it was bought by Gabriel Wells at a Sotheby’s auction for £450 – less than half its reserve price of £1,000. Over 1000 precious and semi-precious stones – rubies, turquoises, emeralds, and others – were used in its making, as well as nearly 5000 pieces of leather, silver, ivory, and ebony inlays, and 600 sheets of 22-karat gold leaf.Īlthough intended to be shipped to New York by Sotheran’s, the booksellers declined to pay the heavy duty imposed on it at US customs. Gracing its gilded cover were three peacocks with bejewelled tails, surrounded by intricate patterns and floral sprays typical of medieval Persian manuscripts, while a Greek bouzouki could be seen on the back.

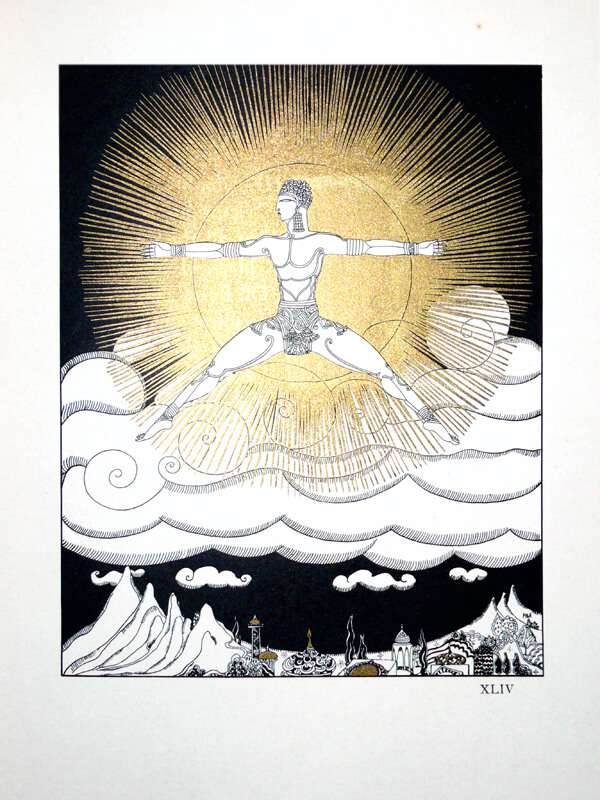

Completed in 1911 after two years of intensive labour, the book – of Edward FitzGerald’s loose Victorian interpretations of Omar Khayyám’s poems, illustrated by Elihu Vedder – came to be known as ‘The Great Omar’, as well as ‘The Book Wonderful’, on account of its sheer splendour. Cost, according to Sotheran’s, was to be no object the bookbinders were given carte blanche to let their imagination go wild and conjure the most bedazzling book the world would ever behold.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)